Upon entering the building of Emmaus Solidarité in a quiet corner of Paris, I waited in the main hall surrounded by the lively sound of people talking. At the center of the meeting place, groups of people chatted over coffee in the morning. Behind the main desk, the receptionist let me know that the director would come to see me in a few minutes.

My colleague Julie, who had just arrived, and I reviewed our project notes when we were interrupted by paramedics running inside with a stretcher. At that moment, the director’s assistant informed us he could only meet with us later; a patron of the shelter just experienced a seizure and the director was occupied with the emergency as the ambulance arrived.

Thrown off by the eventful morning, instead Nathalie would lead us on a tour of the facilities. The shelter for the homeless included bathrooms with showers, offices, resting rooms, a library, and a room for dance and theatre. It offered services ranging from medical counseling to job search assistance and cultural activities. One of about 70 homeless shelters, this one functioned thanks to the work of its 13 staff members, 22 volunteers and 8 interns.

As we made our way around the homeless shelter, patrons that we passed looked curiously at my colleague and me, commenting quietly. Suddenly one of them came upon us to make unwelcomed remarks about our presence there. Taken aback, we were told by Nathalie not to pay any mind. A few moments later, the same man following us approached again, this time more aggressively. Nathalie explained that in certain cases, the image of 2 young women dressed in professional clothing was unusual for the shelter which mainly attracted the poor, middle age men.

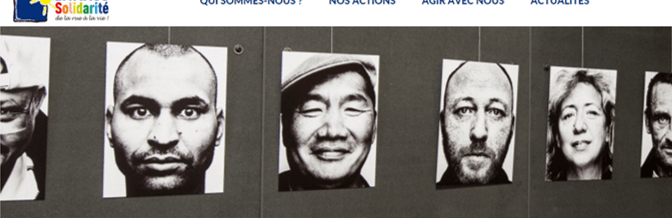

At the end, we were finally able to meet with the director, M. Ledu, who offered insights into the operations and functioning of the homeless shelter. He explained, passerbys and society too often regard people on the street with indifference, deeming them invisible, or worse – blaming them for their current difficult situation. Indeed, this is not very different from the homelessness epidemic in major cities in the USA, particularly New York and Washington DC. As such, the homeless sometimes feel shame and disconnected from the rest of the world. The philosophy of Emmaus Solidarité in Paris is to integrate homeless people into society through culture, sports, and the arts. Hence the shelter participated in the world cup for Homeless people and provided dance and theatre classes for them. At the end of the discussion M. Ledu shared that the shelter received almost all of its funds from the French government, but its support was currently precarious due to unfavorable politics of the refugee crisis. At the end, M. Ledu invited us to speak with and get to know the people in the shelter.

In the main hall, we met Mike. Born in Paris to parents from Guadeloupe, Mike enjoys listening to music. In 2003, he found himself in a difficult housing situation and now frequents the homeless shelter. Despite this, he continues to work temporary positions.

Diop, from Senegal, arrived in France in October 2015. He feels content at the center and especially enjoys acting in theatre. He takes French courses in the center to perfect his written French.

When the guests that we met at the shelter learned that we spoke English, they liked to practice their English with us. Others walked by, watched, or joined the conversation.

At that moment, the assertive man who had been following us on the tour approached. Not knowing whether he would continue with surprising comments, I recognized that he found the meeting interesting and observed without much words. It seemed that he had something he wanted to express. So I turned to him and asked if he wanted to join in.

His name was Ali and he had been frequenting the cent er for 12 years. One day, Ali found himself on the streets after his divorce. Any situation can turn without warning, and anyone can become homeless at any time due to unforeseen or struggling circumstances. Before, Ali worked as a security guard in a store. His favorite part about his previous job was helping elderly or handicapped people navigate the store. Now Ali sells toiletries and items of the like at the shelter and around Paris. In his pastime, he enjoys reading and lends books to his friends at the shelter – his favorite is a collection of well-known works by the French playwright, Molière.

er for 12 years. One day, Ali found himself on the streets after his divorce. Any situation can turn without warning, and anyone can become homeless at any time due to unforeseen or struggling circumstances. Before, Ali worked as a security guard in a store. His favorite part about his previous job was helping elderly or handicapped people navigate the store. Now Ali sells toiletries and items of the like at the shelter and around Paris. In his pastime, he enjoys reading and lends books to his friends at the shelter – his favorite is a collection of well-known works by the French playwright, Molière.

Ali’s opening up showed a need to connect and to share experiences. Often some “write people off” without giving them a chance. Marginalized communities, whose voices are the least heard (the homeless, racial minorities, etc.), are particularly penalized by this attitude. However, there is something about storytelling that allows one to finally present himself to the world – rather than the world judging unduly or inaccurately. Ali, Diop, Mike, Toni, and others who I met exemplify what it means to brave rough times and lead their lives with dignity through challenges thrown at them.

* * *

There is something to be said about the magic of connecting with others – many people in fact fail to connect when they approach others or situations with closed minds or pre-conceived judgements. In the organizations that I engage with, Montage Initiative and Ma Dham shelter in India, homeless women were reluctant to speak with foreign camera crews about their situation as they did not trust the foreigners and their motives. Yet, with my partner organization leaders, we sat down on the floor with these women, ate meals with them, and listened to their stories about their greatest joys and pains being stigmatized as widowed women in India. In a Parisian parallel, earning Ali’s trust, and the trust of the others at the shelter by creating an open environment so they could express their own stories took effort that became a significant moment of connection.

Getting to glimpse, understand, and to some extent feel the aspirations and hurt of another person is a privilege. It demands that the listener put away her own agenda, his preconceived biases, the blame that they attributes based on societal teachings, and instead exercise unbetraying trust – a promise. It is like inviting a guest to enter your house. Only then do we allow others to walk into our shoes, enter our world, empathize, and see our weaknesses and joys.

This understanding then becomes the foundation for effective interaction and informed policies. Emmaus Solidarité certainly faces many pressures – uncertain funding from the government, negative public opinion by those who view refugees and the homeless as a threat, disjointed cooperation with hospitals and other public policy institutions, overworked staff who experience burnout… Yet, the solutions to all these problems require leaders at all levels (from everyday individuals to public office holders) to practice conscientiousness and use their ears and eyes to witness the true situation of their stakeholders, the people that they serve, and those around them.

It is, after all, through the concept of a shared common humanity that some of the best ideas and laws came about: human rights, freedom, good Samaritan, etc. Organizations like Emmaus Solidarité and Montage Initiative capitalize on listening and trust-building to inform better advocacy and policy – always with the aim to make a difference at the heart for those with which we share our stories.

See more on homelessness in Paris and in France.